After abandoning the bike in Coban, I moved through the Guatemalan tourist ring with the rest of the backpacker's crowd and dipped my toes into the open waters of Chicken Bussing. It was a change, and I'd sometimes find myself mentally planning out the heist of a dirt bike, but little by little I was adapting to the crowded, clamorous glory of the system. Nonetheless, when I moved eastward to the less-visited Pacific Slope and found a bus that in a former life was a charter, as opposed the usual re-imagined school buses, I was thrilled. I’d finally found a break.

Onboard, I marveled at the cushioned bucket seats and spacious aisle; this was my first time on a Guatemalan bus

not packed ten to a row. The cushions were stained and torn, the windows held shut with twine, and the blinking Christmas lights around the portrait of Virgin Mary bright enough to make a blind man wince – but it didn't matter. It was un-crowded and there was generous leg room. I settled in and assumed the breezy demeanor of someone flying first class. Off to Santa Lucia…

The two-hour trek southward was dyed in Guatemalan green. The bus whirred past a continuous panorama of cane fields and velvety, emerald mountainsides, interspersed occasionally with tiny, wooden-shack villages peeking out from behind palms and banana trees. The roadside was peppered with wandering horses and cattle; an occasional donkey loaded with corn leaves (for tamales) ambled alongside a sun-beaten

paysano. It was mesmerizing. Hypnotizing, even.

Earlier, the ticket-taker said he’d let me know when we were

nearing my stop, but we’d apparently mis-communicated on the “near” part: When the bus was at a complete stop, I was jolted out of my reverie by urgent shouts of “Santa Lucia! Santa Lucia! Gringa! Santa Lucia!” The driver was not waiting; I hugged my luggage to my body, bolted out of my seat, and charged down the aisle… Sailing down the steps, I had a mental image of the bus inhaling deeply and then SPITTING me out as hard onto the asphalt in Santa Lucia. “Glad I didn’t end up further down the road,” I thought.

Rain was starting to fall so I ducked under the awning of the nearby gas station and dropped my bags onto the ground, unloading the burden of awkwardly positioned weight. I stared out at the watery road and remembered I was thirsty. My hand reached down to grab my pink wallet from the top of my made-for-a-motorcycle-and-not-a-Guatemalan-bus bag … but it wasn’t there. I looked again. Not there. The bag’s contents were hurriedly dumped out, a growing panic peeking its ugly head over the horizon. Oh dear. The wallet was lost. It was on the

bus. Full-blown panic vaulted itself over the horizon and landed feet-first on my doorstep (with a mocking “Ta-da!”). Trouble.

Almost without thinking, I scooped up my luggage and ran it inside to the station attendant (who must have had a very trustworthy face). “I’ll be back in a few hours!” I shouted, sure that if I went after the bus I’d be able to reclaim my wallet. I sprinted out to the road (empty-handed) to intercept the wildly painted chicken bus that had just squealed to a halt in the wet gravel. I jumped onto the stairs and rattled off some garbled, high-speed explanation of the lost wallet and the bus I needed to chase down – adding a pity piece about not having any money for a ticket. “Get in, step up, STEP UP!!” the ticket man shot back – indifferent to my plight or financial situation, concerned only with maintaining a tornado-like pace (even in the pelting rain.) And so began the Great Guatemalan Wallet Caper.

The chase continued along the bumpy highway until a loud CLANK, grrrrr, POP brought us to a complete stop, and the driver and his minions piled out to inspect some mechanical malfunction. My fingers dug their way into the pleathery seat cover; this was not the high-speed pursuit I’d hoped for. But my brooding impatience was interrupted only minutes later when a piece of paper with the name of the bus line I was supposedly looking for was shoved into my hand. “Get off here and take the next bus all the way to Guatemala City! You’ll find your bus there,” they assured me. I jumped down the stairs into the streets of an unknown locale and watched them sputter off, “Guatemala City” ringing in my ears...

These were the two words I did not want to hear. Guatemala City. The guidebooks warn you. Other travelers warn you. Guatemalans warn you. The capital is a den of corruption, wickedness, depravity, lechery, sordidness, filth, muck, smut, crime, sleaze, sin… But, then again, people are always over-exaggerating. I’d been once before and didn’t think it was nearly the inferno it was likened to. And this time my pockets were empty – I literally had

nothing anyone could steal.*

So two hours later, courtesy of another charitable chicken bus, I pulled into Just-Like-They-Say Guatemala City (slightly different from the I’m-Here-With-My-Savvy-Friend Guatemala City I’d visited before). Streets were clogged with agitated pedestrians and angry honking cars, the air visibly gray with exhaust fumes and the haze of general dissatisfaction. Food carts and vendors’ aluminum stalls leaned into each other on the sidewalk, stray dogs picking their way through the confusion. People were moving with purpose but couldn’t get far without stumbling into the chaos – It reminded me of what would happen if you mashed a bunch of ant colonies together and let them untangle themselves.

As soon as my sneakers hit the sidewalk, a taxi mob piled on top of one another to offer me their services in broken English. With a little insistence and a lot of attitude, I broke free of the hagglers’ snare and found directions to the office, then shuffled a few blocks down the street to match the company name on the paper with the corresponding painted sign. A door-less entryway led into a stark white room with a single reception desk. It was empty.

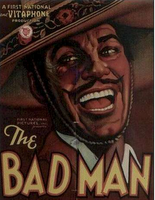

I stood inside for a minute inspecting the deserted workspace, then turned around to see if someone outside might help me. That’s when I first saw him: Bad Man. He’d come in behind me and stood there blinking – his dark, beady eyes were set into a wide, round face, this a rugged terrain full of warty moles extending down his neck and disappearing under a sweat-stained shirt. A bulbous gut stuck so far over his waistline that it looked like he might topple over from being too off-balance. Luckily the office space was open-faced; I might have otherwise bolted away to escape a boiled death in a giant iron cauldron, Bad Man sucking the last scraps of meat off my broken bones and smacking his greasy lips.

He took his place behind the desk and I started to recite my reason for standing in his bare bus office. But he stopped me short to offer me a chair on his side of the desk. I sat down.

Then he asked for the whole story. I told him.

“Well,” he said leaning back in his swivel chair, “there’s nothing we can do tonight. Any bus that arrived here today has turned back around and won’t be back to its home station until late.”

Dread. The buses were supposed to be

there, in Guatemala City, not on the way back to wherever they started from. I knew the question forming on my lips about a CV system was irrelevant. My mind flipped through a million different scenarios, but intuition told me that Bad Man was not likely to go along with any zany schemes of getting in touch with someone before the day was over. “So is there a way to call around in the morning to see if anyone found anything?” I asked, with the tiniest tinge of desperation.

“Of course. I can call to all the offices first thing in the morning.”

My chances of success were crashing like the stock market in a Bush administration (yes, a cheap hit). The longer the wallet was gone, the less likely I seemed to get it back.

“Okay,” I said with a sigh of resignation. “Can I get a phone number here, and I’ll call you from Santa Lucia?”

“Santa Lucia? You’re not thinking of going back there

tonight, are you?”

Silly, silly Bad Man. Of course I’m going back.

“All my luggage is there…” I started in, but was cut off by Bad Man’s urgent cry: “It’ll be dark there by the time you get back!”

Oh, right. Better to be penniless and alone in

Guatemala City when night falls.

Again, I tried with “It will be fine – my things are there…” Again, cut off: “That’s too dangerous!”

This is going to get annoying really fast, I thought. And why couldn’t you have showed this degree of concern over, perhaps, getting my wallet back?

He shifted in his seat a bit and continued. “Here’s what I’ll do – I’ll pay for food and a hotel room for you tonight, then we’ll call around in the morning. If someone has it, you can wait here for it, and if not, you can go back to Santa Lucia in the afternoon.”

Ha! Please, I thought, I know the adage about free lunches. And sleazy men.

“Thank you,” I said with poorly faked gratitude, “but I prefer to go back tonight.”

He put his hand on my knee. “I don’t live in the city either, so I’m staying at the hotel too. We can share a room,” his hand suddenly starting its way up my thigh.

I slapped his wrist away and shot up out of my seat, knocking the chair hard into the desk behind it. I was furious (and revolted). I shot him an icy “No thank you,” eyes narrowed. I paused for a minute, gears churning to come up with a verbal stone-in-the-slingshot to take this Goliath down, to teach Bad Man not to make advances on women in search of their leather-bound identities. But anger was fogging things up. (Having to think in Spanish – also not helping). I turned and walked out, ready to rack the wallet up as a loss and get

out of Guatemala City. No looking back (for fear I might turn into a pillar of salt).

I hurried back down the street, past spray-painted cinderblock walls and vacant storefronts, the insides choked with rubble and garbage. For a third time that afternoon, I climbed a set of chicken bus stairs and was shuffled through as a pro-bono case. I settled in for the long bus ride back to Santa Lucia, still angry that I’d come so far and gotten so little cooperation, but ready to turn attention to my current plight.

A wedding in Michigan was taking me back to the States in two days, so I knew my stint as a vagabond would be relegated to 48 hours. With a well thought-out plan of action, I said to myself, this will be a breeze. My priority was getting to the airport on Thursday, and maybe as a secondary goal, not sleeping in the rain. Though I’d just puppy dog-eyed my way to and from Guatemala City, my floating logic dictated that it would be much harder to actually get to the

airport in Guatemala City. This would require money, I decided. (Certainly it couldn’t be as easy as just asking for a ride on the buses again). And how do you get money without a tin cup, a musical instrument or chips for the slot machine? A job, I said. Yes, I’ll get a job.

Next question: Who will give a bumbling Spanish-speaker with an American passport a job for one day? Again, I flipped through the possibilities, but I envisioned my rejection rate something akin to that of a door-to-door vacuum salesman. Then it dawned on me: The church! The church will give me a job

and a place to sleep. Why? Because they help people who need help. That’s

their job. It was settled. I’d go to the church, ring the bell and wait for one of the nuns to come to the door (because of course all Catholic churches have nuns inside, all day every day), ask for a pew to sleep on, and maybe some work cleaning the floors (or something equally Cinderalla-ish) the next day. That would get me some food and bus money for the airport. I breathed a sigh of relief, happy with my ingenious, “well thought-out” plan.

Halfway through the trip, the youngish man squished in next to me struck up a conversation. “Where are you headed?” he asked. Before I could answer he continued, “I’m sorry to be nosey, it’s just that I’ve never seen someone like you on this bus before.” I mulled over what

like you must mean – tall and white, or bedraggled and desperately confused-looking. I feared it was the latter.

I told him I was headed back to Santa Lucia, and he’d soon garnered the details of my unfortunate day. As the bus started to slow for his stop, he turned to me with a going-out-on-a-limb sort of expression. “I’m going to do something to help you,” he said. “There is someone I know in Santa Lucia…” My hopes jumped: I’m saved! He’s going to point me to someone who will give me a place to sleep (and a job?). I mean, the church was a nice plan, but really…

He took out a business card and scrawled some contact information on the back. “Here,” he said, and I held my hand out for the card like it was the Golden Ticket. “I used to sing in a choir with a youth pastor, and he used to work at the church in Santa Lucia. Take this to the priest and tell that a friend of Fernando Leon sent you – make sure you mention the name of the singing group too.”

Now, I’m not usually one to look a gift horse in the mouth, but last I knew, references weren’t necessary to throw yourself at the mercy of the church. And even in the non-charitable real world where name-dropping is more readily practiced, I’m not sure how far the recommendation of a sort-of acquaintance of an ex-employee will get you. (I envisioned a spoof wherein I stood before the stern entrance of a church, pounding on the thick wooden doors and pleading to be let in, a cloaked, solemn-faced abbot looking down at me through a small hinged eyehole, shaking his head no until I wail, “But I know Rigoberto Vasquez Arana from the singing group “Dia D!” And him then growing chipper and saying, “Well why didn’t you say so earlier?”, throwing open the doors to welcome me in [then offering porridge in a wooden bowl]). (Hollywood really does rot our brains). Nonetheless I took the card, thanked him, and assured him I would email to let him know I’d made it safely.

I got off at the same gas station in Santa Elena, picked up my bags in the office, and headed for the long boulevard towards town and the church, ready to put my plan into action. But I must have been inadvertently flashing the SOS signal (or perhaps it was the I’ve-never-seen-someone-like-you-on-this-bus-before effect) because it took all of three minutes before a twenty-something Guatemalan girl in heels stopped me on the street. “Are you looking for something?” she asked.

I paused. This is going to sound ridiculous, I thought. “Yes. I’m looking for the church”

She raised an eyebrow. “The church? Right now?” It was around 10. “Why?”

“Mmm…” I stalled, trying to come up with a better explanation than “to sleep there.”

“To sleep there.”

She looked at me as if to say, I am not standing in the rain in heels to hear such absurdity. She waited for more; I gave as brief a recap of the day as possible and asked if she could just point me in the right direction… I added some weak supplement about having a card to show to the priest.

The girl gave a sort of half-amused sigh and said, “I’ll walk you there. You shouldn’t be walking around here by yourself.”

But

you are by yourself, I thought. (My, people are a little backwards in this country).

As it happened, her father soon pulled up in his taxicab and once the girl told him my tragic tale, the father insisted that I stay at their house overnight. So in went the wet luggage, out went the church, on went the story.

Next thing I knew I was sitting in a spacious Guatemalan casa, alone at the dining room table, a heaping plate of eggs, beans and tortillas in front of me. “Eat!” The girl’s determined mother called out. “You must be hungry!” She and four of the daughters crowded together in the kitchen, where they had a good vantage point of the starving, destitute American orphan they’d found on the street. I suddenly felt like I fallen on the wrong side of the bars at the zoo. I picked up a tortilla and started nibbling, under their watchful eye.

“Pauvrecita!” I heard them say to each other (as if I couldn’t perfectly hear and understand them). You’d have thought I lost both my legs instead of just a wallet.

But even with the volcano of pity that was spewing down on me, the family was a model of hospitality: They gave me a cup of tea and sat me on a cushy couch in the living room. They pointed out different extended family members hanging in gold-colored frames on the wall (alongside an out-of-place collection of faded portraits of Japanese geishas). They showed me an illegal collection of Olmec artifacts. And then they asked about my plans for the next day. Gulp. Here we go, I thought…

“I’m going to get a job,” I said definitively.

“For one day?” they countered. “Who will give you a job for only one day?”

This sounds more and more preposterous every time I say it. “The church, maybe.”

Again, the eyebrow went up, this time en masse. A rapid-fire Spanish pow-wow delivered a quick family verdict to my predicament: Instead of going to the church, I should go with Oneyda (my heeled rescuer) to Guatemala City (where she worked). I could stay with her there. Oneyda added, “There might be a place where I can get you a job for a day…” as if to appease my hunger to make this a self-sufficient mission. I was in that awkward position where you don’t want to inconvenience anyone by making them go out of their way, but at the same time you think it might inconvenience them even more if you don’t accept their help, so in the end you just smile like a weakling and say yes to whatever they ask. I was on a bus to Guatemala City early the next morning.

We arrived in the same spot I’d arrive the day before, and transferred to another local bus bound for my friend’s apartment. This was when she turned to me and said, “Listen, I think it’s best if I drop you off at my apartment and you can just hang out there for the day. I’ll give you money to get to the airport tomorrow.” I’d sort of assumed this was coming; my puppety head bobbled a compliant “Okay”. Lost were my dreams of earning gainful employment.

As I settled into my new (or continued, rather) leechiness, I noticed out the bus windows that the landscape was changing drastically from the rat hole I’d visited the day before; the roads widened into boulevards, the median greenery was manicured, the skyline shot drastically upwards and sleek, modern high-rises towered over the streets. Glass-encased luxury car dealerships gave light to the slew of Lexus and Audi-branded vehicles (that had replaced the Toyota pick-up trucks) in traffic around us, and the flawlessly groomed women on the sidewalk were toting Louis Vuitton and other logo-ed handbags. Bright, shiny new cafes, movie theaters and shopping malls filled the spaces in-between buildings. It was like I’d entered make-believe world. I turned to Oneyda. “Are we still in Guatemala City?”

“Yes,” she laughed. “C’mon, we’re getting off.”

We got off the bus and walked across the street to a gated fortress where a guard stepped out of a booth to let us pass through into Condolandia. My jaw dropped as we stepped in; I was unaware that anything of this magnificence existed in Guatemala City. My grungy luggage was put on a wheeled cart and taken up four floors to Oneyda’s shared three-bedroom condo, where, instead of manual labor, I spent the day enjoying hot water, flipping through cable channels, chatting with the security guards downstairs and surfing the Internet. I was a Kept Woman.

So in keeping with that spirit, when Oneyda got home from work she invited me out for dinner. “My friend works at the restaurant,” she explained. “It’s where I was thinking of getting you a job.” We took a cab back through the polished neighborhood. And we stepped out in front of (you guessed it)… Hooters, Guatemala City.

By this point, there was nothing that could seem unbelievable. We went inside and ate chicken wings and looked at autographed pictures of American celebrities, like David Spade. And Oneyda’s waitress friend assured me that if ever I wanted to return, she could get me a job. I told her I’d keep it in mind the next time I lost my wallet.

So that’s the story of how I went from sleeping on a pew and mopping floors in a church, to an all-inclusive stay in a GC condo with a meal served by chesty ladies in roller-skates. (It’s not all bad being an orphan). Surprisingly, the family has even invited me back for Christmas – though it’s possible it’s because they think I’ll otherwise be lined up on the “hungry” side of a soup kitchen.

* Minus my physical self. To that point, I recalled research (or perhaps some vague statistics I made up on the spot) showing that kidnapping/abduction victims are usually a) children of vulgarly wealthy people, or b) very small. The obvious conclusion: I’ll most likely not be kidnapped, neither in Guatemala City or anywhere else.